Featured

When other writers and I get together, we sometimes mourn the state of music writing. Not its quality — the music section of any good indie bookstore offers proof of its vigor — but what seems like the reduced number of publications running longer music stories.

In the United States, music coverage now often comes in the form of “20 songs you need right now.” Websites offer features that masquerade as listicles detailing “10 reasons you should listen to so-and-so” or brief posts built around new singles, new videos, artistic feuds, and trending memes. Don’t get me wrong — I need music news, and I love a good list ranking ABBA’s 25 best songs, which is 23 more than I knew existed. I also love being whisked away in a story. Music is the thing that unites all people, and immersive music writing can provide as pleasurable an experience as an hour alone with your streaming service.

This isn’t a uncommon opinion: Many people I know enjoy reading and writing narratives about bands old and new. We love stories about memorable tours, obscure historical incidents, influential songs, personal obsessions, and overlooked music, like Julian Brimmers’s oral history of the short-lived genre Chipmunk Soul. We love career retrospectives and in-depth examinations of gender, race, culture, and our own identities as listeners; same for stories about lost albums, underappreciated musicians, and personalized political pieces like Ellen Willis’s “Beginning to See the Light,” an important dissection of feminism, fandom, and punk rock. These narratives aren’t pegged to a local show, or built around an upcoming album release or Super Bowl performance, which then highlights an increasingly relevant question: Without these news pegs, where do writers send them? For those of us who will likely never write for big slicks like The New Yorker or GQ, and who can’t just write books about the music we want, it’s very difficult to find nationally distributed magazines willing to publish unpegged longform music pieces. Many stories are important enough for us to try to tell, but American newsstands are now practically devoid of music magazines. Where did they go? Assessing the state of music writing requires a look at recent history, which can easily seduce you into discouraging nostalgia.

***

American music journalism started in the 1960s at the Village Voice and Crawdaddy but quickly became so popular that, in 1968, The New Yorker hired Ellen Willis as its first pop music critic. The decade saw an explosion in the genre’s exploration, thriving at newly established titles like Rolling Stone, Creem, Bomp!, and Cheetah, a proliferation which continued well into the 1970s. By the 1980s, it crossed from outlets like the original Bitch: The Woman’s Rock Mag with Bite into the mainstream at Spin, Hullabaloo, The Face, Right On!, MTV, and Black Beat, and at Option, Chunklet, Ray Gun, BAM, and The Rocket in the ’90s. While Rolling Stone first began in the attic of a printing press, nearly going bankrupt within its initial five years, music journalism proved to be extremely profitable.

You didn’t have to search long to find the zine-like Maximumrocknroll and Punk Planet, both as punk in their editorial independence as their musical tastes. If you went to Tower Records, you could pick up their free magazine Pulse!. Even the skate mag Thrasher published band profiles and music news. (One 1989 issue reported: “Rumor from Texas tells of a New Kids on the Block gig gone awry when Kerry King of Slayer threw beer on the New Kids’ lead singer. Kerry and Kid then proceeded to beat each other up while security held the other New Kids back.”) The Source and Vibe were the rap scene’s ultimate taste arbiters, and artists featured in The Source’s “Unsigned Hype” column often became some of the generation’s leading hitmakers, from Notorious BIG to Big Pun and DMX. But hip-hop magazines also featured those bubbling in the underground, rappers that received acclaim in Rap Pages, Stress, Straight No Chaser, and The Bomb Hip-Hop Magazine.

We can’t forget the Beastie Boys’ eclectic six-issue run with Grand Royal, and of course, all the fan zines across the decades, from Flipside and Forced Exposure to Chemical Imbalance. To me, this list of titles shows an unwavering appreciation for music news and stories. As one of Tower Records’ old slogans put it: “No Music, No Life.”

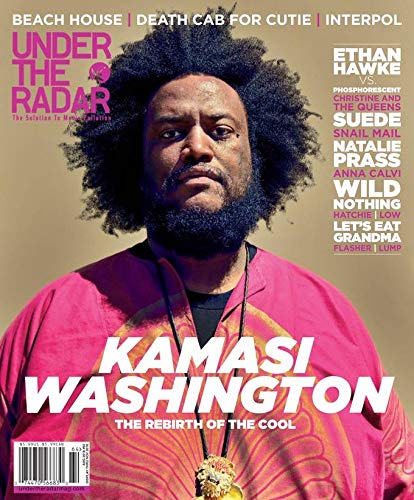

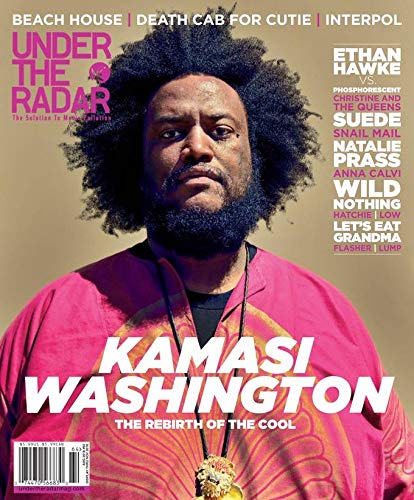

In hindsight, the 1990s and early aughts now resemble the salad days of traditional magazine publishing. It was a time when a writer like Ann Powers could reasonably hope to work as a pop music critic at the Los Angeles Times, and hip-hop journalists could launch their own print magazines like Sacha Jenkins’s ego trip. Da Capo Press’ beloved Best Music Writing anthology was an annual mainstay, and chain bookstores everywhere from Manhattan to Bakersfield stocked a wealth of glossy titles. Spin, Blender, Harp, Magnet, Paste, FILTER, The Big Takeover, Under the Radar, Alternative Press, and Rolling Stone covered rock and pop. The Source, Vibe, Wax Poetics, The Fader, Mass Appeal, XXL, and URB covered hip-hop, soul, jazz, electronic, and R&B. Decibel did metal. Relix did live, improvisational music, No Depression roots music, and Down Beat and JazzTimes sat alongside British stalwarts The Wire and NME.

Hell, there was even a magazine called Ferret Fancy ─ which I read! It had nothing to do with music, but its niche focus embodied these vibrant times. The quality of stories wasn’t universally high, but at least these titles formed a diverse journalistic ecosystem. Alt-weeklies like Chicago Reader, Washington City Paper, and Minnesota City Pages didn’t limit themselves to short criticism or Q&As, and they continued to publish solid music stories, while The Believer loved music so much it eventually launched an annual music issue, following the Oxford American’s lead, which had been publishing music issues with CDs since its 16th issue in 1997. The OA itself followed the lead of CMJ New Music Monthly, which was the first print pub to include a free CD. Stories from many of these publications got reprinted or noted in Best Music Writing.

And though mainstream general interest magazines like Vanity Fair and Esquire, equipped with a greater reach than music magazines, often published what seemed like PR pieces disguised as profiles, they could also surprise you. Vanity Fair contributor David Kamp wrote vividly about L.A.’s infamous Whisky A-Go-Go in 2000. Elizabeth Gilbert profiled Tom Waits for GQ in 2002. For Vibe, Karen R. Good wrote about groupies, materialism, and misogyny in hip-hop in 1999. Mary Gaitskill wrote about her complex attraction to sexist Axl Rose for Details back in 1992. I had barely learned how to pitch magazine stories by 2007, yet it was a glorious time to read and write about music. Then the 2008 recession hit.

You know the details: Residential construction ground to a halt. Manufacturing jobs got cut. Wall Street spiraled into chaos, and Main Street footed the bill. Amid the financial carnage, magazine advertising revenues plummeted. Total ad pages dropped from 255,667 in 2007 to 172,240 by 2010. Magazine newsstand sales had been declining before the recession, but magazines’ advertising revenues precipitously fell from $13.9 billion in 2008 to $10 billion in 2009, in part because online ad revenue kept cutting into print revenue — 31 percent from 22.3 million in 2002 to 15.4 million in 2008. Ad sales in U.S. national magazines fell over 20 percent compared to the previous year during the first quarter of 2009 alone. When advertising shrunk, magazine budgets shrunk. Once reliable publications like Rolling Stone cut back their page numbers, not to mention dimensions. Others like Harp and Blender flat out died. To streamline operations, magazines restructured sales departments and reduced print schedules and staff. Vibe briefly shuttered in 2009, then resumed publishing just six issues a year. Others, like URB, converted from a print to an online magazine. Paste traded print for web in 2010 in an effort to stave off its demise, but only after first installing a failed pay-what-you-wish subscription system modeled after the one Radiohead used for its 2007 album In Rainbows. Spin stayed with its print model until 2012, the year Spin Media’s new CEO laid off 11 editorial staffers and reframed the magazine as “a media company with a print property,” further distancing themselves from print journalism. When the recession’s dust settled, after a period of almost two years, newsstands looked very different, and that’s largely how they’ve remained.

Magazines rise and fall. They lose relevance, their founders move on, or get revamped or shut down by new owners. Some speak for their generation, then the next generation finds a way to speak for themselves. The internet has shaped how current generations speak about music.

***

Before the internet, when people bought records, tapes, and CDs, they found new music from professional music critics, record store clerks, MTV, and word of mouth. This meant that record labels needed magazines to advertise their newest offerings. Labels hung big promotional posters in record stores, and chains like Tower and Virgin had sizeable magazines racks. As music critic Simon Reynolds described that era: “All music and most information were things you literally got your hands on: they came only an analogue form, as tangible objects like records or magazines.” If you wanted to discover records by the loud scuzzy garage bands that mainstream media ignored, like Nights and Days, you read a zine like Jay Hinman’s Superdope. If you wanted to know if the mainstream albums that just came out were good, you read Option, which ran hundreds of reviews. One 1988 issue I have contains 37 pages of album reviews, five pages dedicated to cassette reviews, and a six-page ad from SST records! “The net destroyed the model,” editor Jack Rabid told me via email.

4 out of 5 adults read magazines. (Source: MRI)

4 out of 5 adults read magazines. (Source: MRI) Magazines and magazine ads garner the most attention: BIGresearch studies show that when consumers read magazines they are much less likely to engage with other media or to take part in non-media activities compared to the users of TV, radio or the Internet. (Source: BIGresearch Simultaneous Media Usage Study)

Magazines and magazine ads garner the most attention: BIGresearch studies show that when consumers read magazines they are much less likely to engage with other media or to take part in non-media activities compared to the users of TV, radio or the Internet. (Source: BIGresearch Simultaneous Media Usage Study)